as possibilidades de uma maré vermelha:

origins of struggle and contemporary implications of the brazilian left

30/10/2022

Today, an international gaze is set on Brazil as the country rapidly approaches its presidential election runoffs, following a near-majority vote on October 2nd. Preceded by a neo-fascist Bolsonaro administration – guilty of a genocidal COVID-19 protocol, abhorrent destruction of the Amazon, ruthless execution of human and environmental rights defenders, and rapidly increasing economic inequality resulting from a deepening allegiance to corporate greed over sovereignty and self-determination – the Brazilian political landscape is not only tense, but radically consequential.

For Workers’ Party candidate and former Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, his October 2nd results, polling in with a 48% majority, were just under the threshold needed to win it all in the first round. Yet, there remains much to be said about his popularity, legacy, and energetic capacity to not only transform Brazil, but also geopolitical relations globally. In an effort to diminish Lula’s preparedness, a consequence stemming from his impressive origins as a trade union organizer and political actor, and the magnitudinal strategization of the PT, corporate mainstream media dishonestly framed the first round of elections as a detrimental loss for the Brazilian left. In essence, it obscures the distinct sanguineness and persistent dedication within the nation’s social movements. The gamut of one dimensional, theatrical headlines obscure the overarching, multitudinal struggle incarnate within the masses; this article interpolates as a historical guide of the development of the Brazilian left, the transformative October 30th elections, and its subsequent ramifications.

It illustrates the condition of possibility for the emergence and consolidation of political projects of and for the majority of the population. Under an ongoing phenomenon led by a distinguished political and ideological formation which has undergone various changes throughout the past decades, these political processes not only impact Latin America and the Caribbean, but also the entire world.

Delineating how throughout the past century, Brazil, and nuestra America, has experienced three major cycles of popular resistance by the left, Brazilian sociologist and political scientist Emir Sader demonstrates how the emergence of the Workers’ Party and the breadth of its coalitional relationships are contextualized by the current third cycle of Latin American left mobilization. Manifested concretely through institutional practices and social movements as modes of opposition against global hegemonic capitalism, changes throughout the Brazilian political playground are by no means isolated from neighboring countries; Lula, for both the nation and hemisphere, represents the opportunity of socioeconomic alternatives.

To combat the agendas of foreign capital and US interests, joint work and integration would be radically facilitated through a Lula presidency. The articulation between popular governments and social movements, too, is fundamental, and we observe this in various paises hermanos such as in Colombia, with the groundbreaking win of Pacto Historico, leading to the nation’s first left government, and in Bolivia, whose social movements are closely linked to Luis Arce’s government and have demonstrated a resilient people power that has overcome coup attempts and threats to democracy.

potentialities for geopolitical reconstruction:

As anti-imperialists and internationalists, it comes as no surprise to hear that Brazil, in many ways, finds amongst its palms the future of our planet. A key player as the third largest country in the Americas, it can engage in a critical leadership role; under Lula, it can guide the new wave of left governments throughout the hemisphere and potentially work alongside fellow BRICS member countries like China and Russia, thereby creating a fierce opposition to US government interests which desperately cling to unipolarity and hegemony. As the United States continues to clamor in its ongoing Cold War against China, and its blatant financing of a right wing, Nazi-adjacent government and miltary in Ukraine, its imperialist interests will be confronted by the potentiality of a left wing Latin American bloc which can reify chants for popular self-determination and liberation from foreign, Western interests.

Operating under the complexities of a global phenomenon which reports the weakening of the left and strengthening of the right, a Lula win corresponds to new political imaginaries, such as the creation of a new regional currency (sur), which, as illustrated in a recent interview by former President Dilma Rousseff, could facilitate cross-border trade and holding reserves. This, alongside critical, multipolar leadership in BRICS, makes space for economic realities that no longer are forced to bow down to imperialist orders.

Latin America, marked by its wave of rebellions against violent economic restructuring experienced since the 80s onwards, has the greater potential to contest neoliberal experimentation with one of its most wealthy and large countries under a left governance. It provides the opportunity to reject Washington consensus policies, best defined by development coerced and led by foreign capital. To fight against the privatization of various industries and natural resources, import liberalization, high interest rates, fiscal austerity, and pegged currencies, the articulation between popular governments and social movements is fundamental. Without this critical link, governments remain weak under the pressure of dominant classes, thereby making them unable to meet the demands of the most impoverished and in need. In conjunction with this concrete reality, there is also the necessity of a solid political base; without a strong foundation, popular governments are vulnerable to destabilization through lawfare and coup attempts. What identifies a Lula presidency as necessary and monumental is that it is accompanied by a political party which encapsulates a breadth of experience and capacity, no surprise when the PT is remarked as the largest left party in the capitalist world.

Fundamentally, Brazil and Latin America have no socioeconomic alternatives without critical collaboration and coalescing, something Bolsonaro surely has not prioritized. With recent meetings with the daughter of failed Bolivian coup leader Jeanine Ańez, the Latin American right wing continues to ally itself with white supremacy, misogyny, and class warfare; it is empowered through control of mainstream media and corporate enterprises which have no interest in the wellbeing of our collective peoples and land. Nevertheless, from South to North, projects of political emancipation and self determination persist. The right wing may attack Lula for maintaining diplomatic relationships with socialist countries such as Nicaragua, Venezuela, and Cuba, as illustrated previous Presidential debates, however, new worlds are being constructed in the midst of US aggression and interventionist policies; sanctions and blockades have not been strong enough to tumble the revolutionary efforts of the troika of resistance, and media intimidation alongside with dirty political tactics will not be enough to diminish the potentiality of Lula’s return.

Throughout the hemisphere, we observe massive shifts that speak to capitalism’s incapabilities; what does Lula mean for the Caribbean, for instance, as Haiti suffers brutal interventionist policies, a consequence as the first Latin American country which acheived its liberation through a slave rebellion. Brazil may now have the capacity to reconcile for its military interventionism in the Caribbean nation, opening doors that reject the United States’ clamp on Black self-determination in the region. Further, we can begin to ask how Lula’s relationship with Cuba, who in September passed a new family code which recognizes same-sex marriage, broader rights and protections for the elderly, and measures against gender violence, feedback into contemporary Brazilian society? What role will Brazil under a left governance play in terms of fighting back economic warfare and building international solidarity?

And what about Central America, so overlooked and yet a fundamental connection between the South and North? Panama, with her days marked by historic strikes against anti-worker policies propelled by President Laurentino Cortizo. Guatemala, who, like Brazil, has a significant Indigenous and Native community, remains in permanent mobilization against abuses by President Alejandro Giammatte. What new ties can be fortified by pueblos distintos, los cuales a la misma vez comparten tanta historia y lucha. Nicaragua, um país que precisa de solidariedade, which has built radical food sovereignty and shares such deep ties with Brazil’s Movimento Sem Terra.

The reality stands that under a more progressive government, the potential for Latin America and Caribbean unification is heightened; possibilities to struggle and fight are endless in the thick of an international phenomenon which devalues life and sovereignty.

Surely, Lula’s governance will not be as radical per se as Cuba, however, the successes and origins of his political trajectory, accompanied by the struggles set forth from organizations such as the CUT, MST, and other left wing formations, will combat the hunger, poverty, and alienation which has presented itself dramatically under the violent, neoliberal administration of Jair Bolsonaro.

on historical memory and legacy; formation of contemporary left politics in brazil:

Cada um procura melhorar…

E o Partido Ajuda…

Ninguém nasce feito, nem nasce bom nem ruim…

O Partido ajuda, faz a gente, de forma indireta.

Jorge Amado

E o Partido Ajuda…

Ninguém nasce feito, nem nasce bom nem ruim…

O Partido ajuda, faz a gente, de forma indireta.

Jorge Amado

Brazil's left forces are particular because its development was subdued compared to neighboring countries; by the time the US backed military coup of 1964 took place, the fragility of the left enabled the regime to undergo a rigid economic expansion from 1967 to 1973. Adopting an economic model based on exports and the luxury-goods sector, there was a shift in the labor force, with manufacturing conurbations sprawling throughout São Paulo. Huge industrial investment was also observed in Rio de Janeiro, with the implementation of nuclear plants in Angra dos Reis and the construction of the Ponte Rio-Niterói; these operations were extended to Amazonas too, with the construction of the Transamazônica, a gigantic road that connects the entire country from East to West, and the creation of an industrial complex located in the heart of the Brazilian Amazon forest region.

Inherent to the cyclical crises of capitalism and imperialism, the exploitation of labor and natural resources in Brazil was justified through outward capital surfacing not as investment but in the form of fluctuating interest rates. Fragile and unstable, mirroring capitalism in its entirety, the boom of rising interest rates in 1979, alongside with the nation’s heavy industrialization, brought a shift in the “composition of the labor force”, unfolding a new left and the birth of the PT.

The vigorous emergence of the party in 1980 is represented by three key groups: peasant farmers, base organizations of the Catholic Church, and young trade-union leaders from automobile manufacturing plants located in the ABC zone within the periphery of São Paulo. The range, and subsequent power, of the PT’s base is further reflected in the involvement of unionists in oil and banking sectors, former militants, and radicalized intellectuals. A heterogeneous cohort, its political formation expanded through strategic relationships maintained with groups such as CUT (Central Única dos Trabalhadores) and the MST (Movimento Sem Terra). The impulse of grassroots trade unionism, although illegal under the dictatorship, resulted in an emerging new generation of leaders including northeasterner and former lathe operator Lula, who carried out a series of strikes that broke the regime’s wage policy.

A decade later, marked by the fall of the military dictatorship in 1985, the unification of peasant farmers, Catholic liberation theologists, and unions formed within manufacturing, oil, and banking sectors set the stage for the PT’s growing influence. Although unsuccessful in securing a win during the 1989 presidential elections, Brazil, and the hemisphere at large, began to experience a wave of rebellions propelled by the neoliberal economic restructuring that characterized the 1980s. For the PT, the democratization of Brazil brought a host of new challenges: the fall of the dictatorship concluded a specific model of capital accumulation, replaced by a liberal democracy that echoed Washington consensus policies that brought no social or economic reforms. Opposing the conservative model of transition but failing to call for an alternative comprehension of democracy, it was not until 1989 that the party was able to present itself as a palpable alternative for national government. At this moment, the international stage underwent the consolidation of neoliberal hegemony, representing for Brazil a surge of privatizations, mergers and acquisitions of Brazilian firms by foreign multinationals. Alongside the displacement of national capital, deindustrialization, and pegging the currency to the dollar, the PT’s working class base was severely impacted by rising unemployment and the weakening of trade unionism. Nevertheless, Lula and the PT continued to enrich their growing presence within political institutions, setting the stage for his successful election in 2002.

building organizational power:

How the party was capable of garnering unparalleled institutional power at the turn of the century is a lesson in the importance of party organization. For Lula to win in 2002, the PT shifted its focus to the Northeast. National leadership deliberately expanded the party’s local infrastructure to carry out a stronger presence in the area, thereby resulting in the rejection of traditional clientelism which dominated the area. Preparations were facilitated due to an increase in party finances, permitting for a strengthening of the party label and national campaign infrastructure. On the ground electoral mobilization was materialized through two means: party activists, who engaged in organizing rallies, door to door distribution of written information, and transporting people to polling booths, and party offices, which managed financial, material, and logistical support.

For the North and Northeast, these preparations were groundbreaking, as it transformed ideological inclinations so dramatically that now these regions are PT strongholds. The growth and sustainability of the PT is not solely because of the increase in electoral support, but also because of its long term organizational strength, which was able to overcome three unsuccessful Presidential campaigns (1989, 1994, 1998). Therefore, we can come to the conclusion that organizational strength in conjunction with electoral support facilitates contemporary parties to survive in the long run. By focusing on the poorest regions in the nation, PT’s political outreach led to huge electoral gains that benefitted a region traditionally marginalized and ignored domestically.

During Lula’s first presidency, for example, we saw the creation of Bolsa Família, a conditional cash transfer program of “unprecedented scope in Brazilian history” that primarily focused on households which were headed by single mothers. Further, the program provided US$60 or less to poor families and children of recipient families were required to attend public school and receive periodic vaccinations/health screenings. By 2006, the program reached 11 million poor families (40 million citizens). For the Northeast, which is home to ¼ of the national population, households received ½ of all Bolsa Familia disbursements. Impacts included but were not limited to stimulation of local family and community related economies through increased consumer spending and a perception of Lula that was not only positive but continues to play out significant consequences in the upcoming Presidential election.

Noted organizational power building has proved to be a fortified strategy which has maintained itself as a legitimate mode of securing legitimacy and providing real gains to marginalized and working class people in Brazil. The attention and work enacted in the Northeast, for example, is significant because it has the highest concentration of Afro-Brazilians; understanding that racialized capitalism alienates and exploits Black people, surely, neoliberal economic policies by previous administrations as well as the Bolsonaro government, has brought painful realities to the surface. It is essential to note that this region was the center of agricultural production during the period of slavery in Brazil, thus accentuating the legacy of oppression and exploitation in the region. Only through a Lula administration will popular people power have the capacity to transform material conditions for vulnerable sectors of the country.

2002 operated as a pivotal year for the PT, and not only was it able to dramatically expand its outreach in the North and Northeast, but further, it was able to work alongside with critical organizations such as the MST, thereby creating environmental policy that challenged pervasive, extractive economic protocol which endangers land, food, and water sovereignty. Part of Lula’s current campaign is marked by his commitment to combat deforestation and constitute a socio-environmental agenda. This comes as no surprise – his first cabinet in 2003 incorporated Amazon rainforest activist Marina Silva as Minister of the Environment, whose policies by 2012 reduced the loss of forests by 84% (Jeantet et Maisonnave, 2022).

Unification of grassroots movements and the progressive governance of the PT not only meant positive transformations surrounding economic stimulation for impoverished peoples and the environment, but his legacy is also marked by greater accessibility and equity to education. This was not only facilitated through the creation of Bolsa Familía, but also through an expansion and interiorization of federal universities from 2003-2014.

To fully examine the growth of not only Lula as a world leader but also the work enacted by the PT and left organizations would necessitate a separate article, nonetheless, these brief case studies illustrate the impact of Lula’s previous administration and new alternatives against Bolsonaro’s detrimental policies which have regressed the country.

consequences, contradictions, and challenges

¡Qué espanto causa el rostro del facismo!

Llevan a cabo sus planes con precisión artera

sin importarles nada.

La sangre para ellos son medallas.

La matanza es acto de heroísmo.

¿Es este el mundo que creaste, Dios mío?

¿Para esto tus siete días de asombro y trabajo?

Victor Jara

Llevan a cabo sus planes con precisión artera

sin importarles nada.

La sangre para ellos son medallas.

La matanza es acto de heroísmo.

¿Es este el mundo que creaste, Dios mío?

¿Para esto tus siete días de asombro y trabajo?

Victor Jara

Anxieties loom as the election’s ambiguity poses dire directional consequences for the next four years. Yet, having been on the ground for the past month, traveling to and from São Paulo and Rio, the political landscape in Brazil is uncertain and yet optimistic that Lula can win it all. The strength of the Brazilian left is marked by the coalitional support currently backing Lula; with 7 parties, he has the broadest candidacy since 1989. Nevertheless, the media landscape, operating as per usual, has made it challenging for the left to distribute factual information which is critical towards pushing the vote to the PT. It is no doubt that during the 2018 election, Bolsonaro significantly benefited from the misinformation disseminated by WhatsApp and other social media platforms. Many of his supporters, for instance, pertain to the notion that Lula is a ‘criminal’ due to the 580 days he spent in prison on false corruption charges that were not only dismissed, but ruled that former judge and former member of Bolsonaro’s government, Sergio Moro, had clear political intentions regarding the convictions. Nonetheless, the right wing narrative surrounding him, alongside with racist dog whistles against marginalized communities that are more likely to support Lula, have all played an important role in the midst of a media landscape that promotes melodrama and false framing.

Bolsonaro has furthered his use of media manipulation in order to repeatedly make unsubstantiated claims that Brazil’s internationally-respected electronic voting system is vulnerable to fraud. These claims have been spread by right wing allies in the US, such as Steve Bannon. Adjacent to the strategies of the US right wing, there remains a strong inclination that he will follow the playbook set forth by his collaborator and hero Donald Trump and declare, without evidence, that the results were fraudulent. Although the US has its hands tied with its ongoing conflicts in China and Russia and may not immediately intervene as it has in previous, if there is anything October 2nd highlighted, it’s that the National Congress remains conservative, thereby opening up the potential for lawfare and a coup attempt.

Right wing mobilization and violence remains as potential emboldened consequences; the far-right president has a long standing friendship with Roberto Jefferson, who recently threw grenades and shot at federal police. Bolsonaro lied about having taken a single photo with Jefferson, and even went to the extent of utilizing automated accounts of social media to tweet the same decades-old picture of Jefferson next to Lula to try and erase the connections between the right wing allies. Nevertheless, the Jefferson and Bolsonaro families have maintained a long relationship engulfed in corruption, money laundering, and various labor violations. Incarnate with violence, Jefferson’s attack on Sunday was further facilitated through the CAC (Collectors, Shooters and Hunters) loophole. Instituted by the Bolsonaro administration, it allows any civilian to purchase equipment previously restricted to police and armed forces. It remains certain that the explosive and dangerous tactics of the right wing, not only limited by their use of armed weapons but also through undemocratic rhetoric, attacks on fair reporting, and red scare campaigning, the right wing is doing all it can to maintain power.

To further illustrate, former mayor of São Paulo Fernando Haddad stated in a recent interview that although the polls demonstrate Lula is in the lead, Bolsonaro plays dirty politics. We can come to the conclusion that these dishonest political operations are heightened due to the right wing’s accessibility to state equipment and private financing, which will demonstrate class solidarity to those who have grossly enriched themselves on the labor and land of the people.

And certainly, what is to be done surrounding the consequences of the military police which dominates the right wing in the nation: in Brazil we can observe the militarization of politics vs the politicization of the military. In the city of Maceió, located in the Northeast, we examine the ways in which the federal police “acts like the Gestapo” according to senator Renan Calheiros who denounced the Bolsonaro-backed coup attempt against Paulo Dantas, current governor of the state of Alagoas, earlier this month.

And too, we cannot forget about Bolsonaro’s utilization of what has been argued as the “world’s biggest corruption scheme”. In an attempt to buy out congress and the 2022 presidential election, there has been the use of a Secret Budget which has resulted in the loss of resources for sensitive areas of the Brazilian state, such as health and education. Resources in place for the public sector have been transferred for what are essentially bribes for Bolsonaro’s congressional base. With a Congress that refuses to invoke an investigation surrounding corruption charges, the Secret Budget explains in part why voters supported Lula but gave Bolsonaro the largest caucus in the Chamber of Deputies. Funding deputies from the “Centrão”, which is formed by the Liberal Party, Progressive Party, and Republicans. Within 30 days, elected politicians can engage in what is referred to as “janela partidária”, allowing them to jump from one political party to another – the consequence resulting in 99 Liberal Party federal deputies elected to the legislature on October 2nd.

Challenges posed under the current political playground are not only domestic in nature, but also incorporate geopolitical factors: Brazil, like the rest of the hemisphere, remains vulnerable under the motivations of neoliberal, imperialist interests that threaten democracy and self-determination.

in politics, there are no empty spaces: what it takes to win

Calma, porque tenemos prisa

y el trecho es duro de andar,

Calma, pero adémas constancia

para llegar, para llegar, para llegar.

Calma. Calma y algo más.

Noel Nichola

y el trecho es duro de andar,

Calma, pero adémas constancia

para llegar, para llegar, para llegar.

Calma. Calma y algo más.

Noel Nichola

If October 2nd can illuminate the long tunnel before us, it is that the strength of the Brazilian left has recently undergone a consolidation process through strategic coalitional relationship building. Alongside with polls that favor Lula we find possibilities of processes which are oriented towards sovereignty and popular power through emerging organizations which center solidarity and democracy. Not only leading up to the campaign, but also historically, the Brazilian left maintains the opportunity to develop practices which manifest the emergence and consolidation of political projects of and for the majority of the population.

There are no empty spaces in politics, especially when we think about the fact that one of the biggest mistakes of the PT was its failure in providing acute attention and dedication to Evangelical communities, which were vulnerable to a co-optation operation headed by Bolsonaro and other hardline right wingers. Thankfully Lula and the left realized that and have been trying to reintegrate this important part of the population in its campaigning. Evangelicals are by no means a monolith, and although the majority supported Bolsonaro in the 2018 election, research conducted by the DataFolha Institute demonstrates that not all Evangelicals in the country are rallying their support for the far right presidential candidate. As the fastest growing religious community, composing 31% of the national population, key organizers and local activists have made it a priority to provide accurate information for Evangelical voters as the election creeps up.

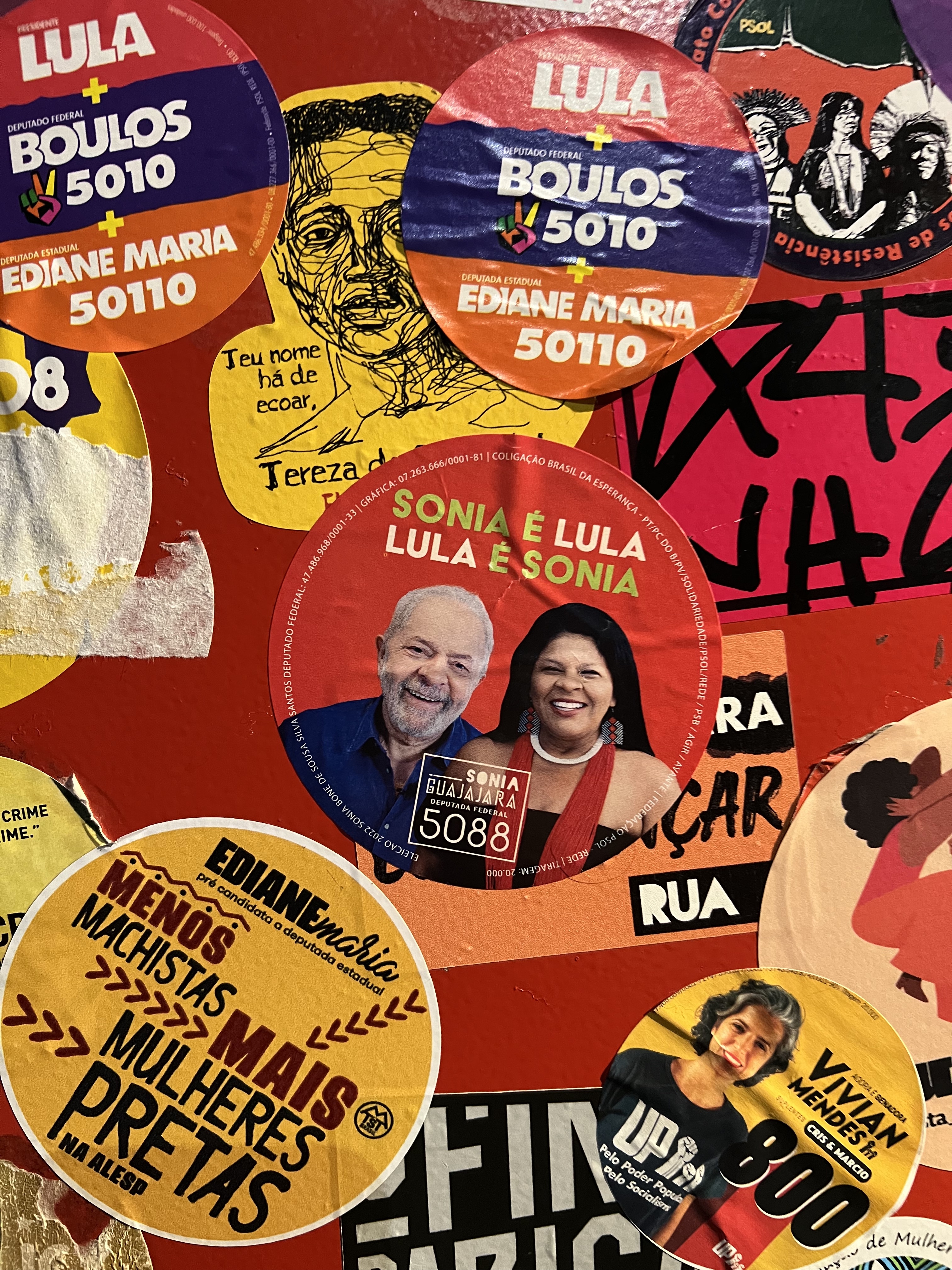

Institutional and grassroots cooperation in Latin America constructs avenues to contest the thanatological dynamics of the current capitalist mode of production; for Brazil, left leadership is not only exemplified through Lula and the PT, but also through the introduction of critical socialist actors such as Guilherme Boulos, an MTST (Movimento dos Trabalhadores Sem Teto) leader who in the first round of elections received over a million votes. The MTST has played a critical role in developing strong leaders, not only Boulos, but also recently elected deputies such as Rosa Amorim, who was elected to the Pernambuco legislature and the first deputy to have grown up on an MTST settlement. There’s also the impact of Ediane Maria's successful election, guided by the formación of the MTST. Maria, as a mother of three and a queer Black woman, represents an ongoing struggle for working class folks like her; she, like recently elected Colombian Vice President Francia Marquez, is also a former domestic worker, and the first domestic worker to be elected. The crux of solidarity maintained throughout the campaigns doesn’t just stop there, for instance, candidates like Sônia Guajajara, an Indigenous woman whose campaign proved successful, and Erica Hilton, the first Black trans woman to be elected member of the legislature, are also representative of the ways in which historically marginalized folks are able to garner institutional power in the midst of, of course, all of the contradictions embedded into electoral politics.

Certainly, struggle is not easy nor is it clear cut, but with the PT electing 80 parliamentarians, and with a horizon that, on the week of Lula’s birthday, may also represent a globally impactful win, there are various avenues which can provide breathing room not only for Brazillians, but working class people internationally.